Nelson Mandela - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

SOME EXAMPLES OF NELSON MANDELA IN HIS LATER LIFE AS THE UNITER.

SOME EXAMPLES OF NELSON MANDELA IN HIS LATER LIFE AS THE UNITER.

Victor Verster Prison and release: 1988–1990

Recovering from tuberculosis caused by dank conditions in his cell,[174] in December 1988 Mandela was moved toVictor Verster Prison near Paarl. Here, he was housed in the relative comfort of a warder's house with a personal cook, using the time to complete his LLB degree.[175] There he was permitted many visitors, such as anti-apartheid campaigner and longtime friend Harry Schwarz.[176][177] Mandela organised secret communications with exiled ANC leader Oliver Tambo.[178] In 1989, Botha suffered a stroke, retaining the state presidency but stepping down as leader of the National Party, to be replaced by the conservative F. W. de Klerk.[179] In a surprise move, Botha invited Mandela to a meeting over tea in July 1989, an invitation Mandela considered genial.[180] Botha was replaced as state president by de Klerk six weeks later; the new president believed that apartheid was unsustainable and unconditionally released all ANC prisoners except Mandela.[181] Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, de Klerk called his cabinet together to debate legalising the ANC and freeing Mandela. Although some were deeply opposed to his plans, de Klerk met with Mandela in December to discuss the situation, a meeting both men considered friendly, before releasing Mandela unconditionally and legalising all formerly banned political parties on 2 February 1990.[182] The first photographs of Mandela were allowed to be published in South Africa for 20 years.[183]

Leaving Victor Verster on 11 February, Mandela held Winnie's hand in front of amassed crowds and press; the event was broadcast live across the world.[184] Driven to Cape Town's City Hall through crowds, he gave a speech declaring his commitment to peace and reconciliation with the white minority, but made it clear that the ANC's armed struggle was not over, and would continue as "a purely defensive action against the violence of apartheid." He expressed hope that the government would agree to negotiations, so that "there may no longer be the need for the armed struggle", and insisted that his main focus was to bring peace to the black majority and give them the right to vote in national and local elections.[185] Staying at the home of Desmond Tutu, in the following days Mandela met with friends, activists, and press, giving a speech to 100,000 people at Johannesburg's Soccer City.[186]

End of apartheid

Main article: Negotiations to end apartheid in South Africa

Early negotiations: 1990–1991

Mandela proceeded on an African tour, meeting supporters and politicians in Zambia, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Libya and Algeria, continuing to Sweden where he was reunited with Tambo, and then London, where he appeared at theNelson Mandela: An International Tribute for a Free South Africa concert in Wembley Stadium.[187] Encouraging foreign countries to support sanctions against the apartheid government, in France he was welcomed by PresidentFrançois Mitterrand, in Vatican City by Pope John Paul II, and in the United Kingdom he met Margaret Thatcher. In the United States, he met President George H.W. Bush, addressed both Houses of Congress and visited eight cities, being particularly popular among the African-American community.[188] In Cuba he met President Fidel Castro, whom he had long admired, with the two becoming friends.[189] In Asia he met President R. Venkataramanin India, President Suharto in Indonesia and Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad in Malaysia, before visiting Australia to meet Prime Minister Bob Hawke and Japan; he notably did not visit the Soviet Union, a longtime ANC supporter.[190]

In May 1990, Mandela led a multiracial ANC delegation into preliminary negotiations with a government delegation of 11 Afrikaner men. Mandela impressed them with his discussions of Afrikaner history, and the negotiations led to the Groot Schuur Minute, in which the government lifted the state of emergency. In August Mandela – recognising the ANC's severe military disadvantage – offered a ceasefire, the Pretoria Minute, for which he was widely criticised by MK activists.[191] He spent much time trying to unify and build the ANC, appearing at a Johannesburg conference in December attended by 1600 delegates, many of whom found him more moderate than expected.[192] At the ANC's July 1991 national conference in Durban, Mandela admitted the party's faults and announced his aim to build a "strong and well-oiled task force" for securing majority rule. At the conference, he was elected ANC President, replacing the ailing Tambo, and a 50-strong multiracial, mixed gendered national executive was elected.[193]

Mandela was given an office in the newly purchased ANC headquarters at Shell House, central Johannesburg, and moved with Winnie to her large Soweto home.[194] Their marriage was increasingly strained as he learned of her affair with Dali Mpofu, but he supported her during her trial for kidnapping and assault. He gained funding for her defence from the International Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa and from Libyan leaderMuammar Gaddafi, but in June 1991 she was found guilty and sentenced to six years in prison, reduced to two on appeal. On 13 April 1992, Mandela publicly announced his separation from Winnie. The ANC forced her to step down from the national executive for misappropriating ANC funds; Mandela moved into the mostly white Johannesburg suburb of Houghton.[195] Mandela's reputation was further damaged by the increase in "black-on-black" violence, particularly between ANC and Inkatha supporters in KwaZulu-Natal, in which thousands died. Mandela met with Inkatha leader Buthelezi, but the ANC prevented further negotiations on the issue. Mandela recognised that there was a "third force" within the state intelligence services fuelling the "slaughter of the people" and openly blamed de Klerk – whom he increasingly distrusted – for the Sebokeng massacre.[196] In September 1991 a national peace conference was held in Johannesburg in which Mandela, Buthelezi and de Klerk signed a peace accord, though the violence continued.[197]

CODESA talks: 1991–1992

The Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA) began in December 1991 at the Johannesburg World Trade Center, attended by 228 delegates from 19 political parties. Although Cyril Ramaphosa led the ANC's delegation, Mandela remained a key figure, and after de Klerk used the closing speech to condemn the ANC's violence, he took to the stage to denounce him as "head of an illegitimate, discredited minority regime". Dominated by the National Party and ANC, little negotiation was achieved.[198] CODESA 2 was held in May 1992, in which de Klerk insisted that post-apartheid South Africa must use a federal system with a rotating presidency to ensure the protection of ethnic minorities; Mandela opposed this, demanding a unitary system governed by majority rule.[199] Following the Boipatong massacre of ANC activists by government-aided Inkatha militants, Mandela called off the negotiations, before attending a meeting of the Organisation of African Unity in Senegal, at which he called for a special session of the UN Security Council and proposed that a UN peacekeeping force be stationed in South Africa to prevent "state terrorism". The UN sent special envoy Cyrus Vance to the country to aid negotiations.[200] Calling for domestic mass action, in August the ANC organised the largest-ever strike in South African history, and supporters marched on Pretoria.[201]

Following the Bisho massacre, in which 28 ANC supporters and one soldier were shot dead by the Ciskei Defence Force during a protest march, Mandela realised that mass action was leading to further violence and resumed negotiations in September. He agreed to do so on the conditions that all political prisoners be released, that Zulu traditional weapons be banned, and that Zulu hostels would be fenced off, the latter two measures to prevent further Inkatha attacks; under increasing pressure, de Klerk reluctantly agreed. The negotiations agreed that a multiracial general election would be held, resulting in a five-year coalition government of national unity and a constitutional assembly that gave the National Party continuing influence. The ANC also conceded to safeguarding the jobs of white civil servants; such concessions brought fierce internal criticism.[202] The duo agreed on an interim constitution, guaranteeing separation of powers, creating a constitutional court, and including a US-style bill of rights; it also divided the country into nine provinces, each with its own premier and civil service, a concession between de Klerk's desire forfederalism and Mandela's for unitary government.[203]

The democratic process was threatened by the Concerned South Africans Group (COSAG), an alliance of far-right Afrikaner parties and black ethnic-secessionist groups like Inkatha; in June 1993 the white supremacist Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB)attacked the Kempton Park World Trade Centre.[204] Following the murder of ANC leader Chris Hani, Mandela made a publicised speech to calm rioting, soon after appearing at a mass funeral in Soweto for Tambo, who had died from a stroke.[205] In July 1993, both Mandela and de Klerk visited the US, independently meeting President Bill Clinton and each receiving the Liberty Medal.[206] Soon after, they were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in Norway.[207] Influenced by young ANC leader Thabo Mbeki, Mandela began meeting with big business figures, and played down his support for nationalisation, fearing that he would scare away much-needed foreign investment. Although criticised by socialist ANC members, he was encouraged to embrace private enterprise by members of the Chinese and Vietnamese Communist parties at the January 1992 World Economic Forum in Switzerland.[208] Mandela also made a cameo appearance as a schoolteacher reciting one of Malcolm X's speeches in the final scene of the 1992 filmMalcolm X.[209]

General election: 1994

Main article: South African general election, 1994

With the election set for 27 April 1994, the ANC began campaigning, opening 100 election offices and hiring advisorStanley Greenberg. Greenberg orchestrated the foundation of People's Forums across the country, at which Mandela could appear; though a poor public speaker, he was a popular figure with great status among black South Africans.[210] The ANC campaigned on a Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) to build a million houses in five years, introduce universal free education and extend access to water and electricity. The party's slogan was "a better life for all", although it was not explained how this development would be funded.[211] With the exception of the Weekly Mail and the New Nation, South Africa's press opposed Mandela's election, fearing continued ethnic strife, instead supporting the National or Democratic Party.[212] Mandela devoted much time to fundraising for the ANC, touring North America, Europe and Asia to meet wealthy donors, including former supporters of the apartheid regime.[213] He also urged a reduction in the voting age from 18 to 14; rejected by the ANC, this policy became the subject of ridicule.[214]

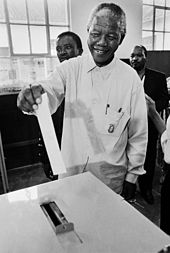

Concerned that COSAG would undermine the election, particularly in the wake of the Battle of Bop and Shell House Massacre – incidents of violence involving the AWB and Inkatha, respectively – Mandela met with Afrikaner politicians and generals, including P.W. Botha, Pik Botha and Constand Viljoen, persuading many to work within the democratic system, and with de Klerk convinced Inkatha's Buthelezi to enter the elections rather than launch a war of secession.[215] As leaders of the two major parties, de Klerk and Mandela appeared on a televised debate; although de Klerk was widely considered the better speaker at the event, Mandela's offer to shake his hand surprised him, leading some commentators to consider it a victory for Mandela.[216] The election went ahead with little violence, although an AWB cell killed 20 with car bombs. As widely expected, the ANC won a sweeping victory, taking 62 percent of the vote, just short of the two-thirds majority needed to unilaterally change the constitution. The ANC was also victorious in 7 provinces, with Inkatha and the National Party each taking another.[217] Mandela voted at the Ohlange High School in Durban, and though the ANC's victory assured his election as President, he publicly accepted that the election had been marred by instances of fraud and sabotage.[218]

Presidency of South Africa: 1994–1999

Main article: Presidency of Nelson Mandela

The newly elected National Assembly's first act was to formally elect Mandela as South Africa's first black chief executive. His inauguration took place in Pretoria on 10 May 1994, televised to a billion viewers globally. The event was attended by 4000 guests, including world leaders from disparate backgrounds.[219] Mandela headed a Government of National Unity dominated by the ANC – which alone had no experience of governance – but containing representatives from the National Party and Inkatha. Under the Interim Constitution, Inkatha and the NP were entitled to seats in the government by virtue of winning at least 20 seats. In keeping with earlier agreements, de Klerk became first Deputy President, and Thabo Mbeki was selected as second.[220] Although Mbeki had not been his first choice for the job, Mandela grew to rely heavily on him throughout his presidency, allowing him to organise policy details.[221] Moving into the presidential office at Tuynhuys in Cape Town, Mandela allowed de Klerk to retain the presidential residence in the Groote Schuur estate, instead settling into the nearby Westbrooke manor, which he renamed "Genadendal", meaning "Valley of Mercy" in Afrikaans.[222] Retaining his Houghton home, he also had a house built in his home village of Qunu, which he visited regularly, walking around the area, meeting with locals, and judging tribal disputes.[223]

Aged 76, he faced various ailments, and although exhibiting continued energy, he felt isolated and lonely.[224] He often entertained celebrities, such as Michael Jackson, Whoopi Goldberg, and the Spice Girls, and befriended ultra-rich businessmen, like Harry Oppenheimer of Anglo-American, as well as QueenElizabeth II on her March 1995 state visit to South Africa, resulting in strong criticism from ANC anti-capitalists.[225] Despite his opulent surroundings, Mandela lived simply, donating a third of his 552,000 rand annual income to the Nelson Mandela Children's Fund, which he had founded in 1995.[226] Although speaking out in favour of freedom of the press and befriending many journalists, Mandela was critical of much of the country's media, noting that it was overwhelmingly owned and run by middle-class whites and believing that it focused too much on scaremongering around crime.[227] Changing clothes several times a day, after assuming the presidency, one of Mandela's trademarks was his use of Batik shirts, known as "Madiba shirts", even on formal occasions.[228]

In December 1994, Mandela's autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, was finally published.[229] In late 1994 he attended the 49th conference of the ANC in Bloemfontein, at which a more militant National Executive was elected, among them Winnie Mandela; although she expressed an interest in reconciling, Nelson initiated divorce proceedings in August 1995.[230] By 1995 he had entered into a relationship with Graça Machel, a Mozambican political activist 27 years his junior who was the widow of former president Samora Machel. They had first met in July 1990, when she was still in mourning, but their friendship grew into a partnership, with Machel accompanying him on many of his foreign visits. She turned down Mandela's first marriage proposal, wanting to retain some independence and dividing her time between Mozambique and Johannesburg.[231]

National reconciliation

Presiding over the transition from apartheid minority rule to a multicultural democracy, Mandela saw national reconciliation as the primary task of his presidency.[232] Having seen other post-colonial African economies damaged by the departure of white elites, Mandela worked to reassure South Africa's white population that they were protected and represented in "the Rainbow Nation".[233] Mandela attempted to create the broadest possible coalition in his cabinet, with de Klerk as first Deputy President. Other National Party officials became ministers for Agriculture, Energy, Environment, and Minerals and Energy, and Buthelezi was named Minister for Home Affairs.[234] The other cabinet positions were taken by ANC members, many of whom – like Joe Modise, Alfred Nzo, Joe Slovo, Mac Maharaj and Dullah Omar – had long been comrades, although others, such as Tito Mboweni andJeff Radebe, were much younger.[235] Mandela's relationship with de Klerk was strained; Mandela thought that de Klerk was intentionally provocative, and de Klerk felt that he was being intentionally humiliated by the president. In January 1995, Mandela heavily chastised him for awarding amnesty to 3,500 police just before the election, and later criticised him for defending former Minister of Defence Magnus Malan when the latter was charged with murder.[236]

Mandela personally met with senior figures of the apartheid regime, including Hendrik Verwoerd's widow Betsie Schoombie and the lawyer Percy Yutar; emphasising personal forgiveness and reconciliation, he announced that "courageous people do not fear forgiving, for the sake of peace."[237] He encouraged black South Africans to get behind the previously hated national rugby team, the Springboks, as South Africa hosted the 1995 Rugby World Cup. After the Springboks won an epic final over New Zealand, Mandela presented the trophy to captain Francois Pienaar, an Afrikaner, wearing a Springbok shirt with Pienaar's own number 6 on the back. This was widely seen as a major step in the reconciliation of white and black South Africans; as de Klerk later put it, "Mandela won the hearts of millions of white rugby fans."[238] Mandela's efforts at reconciliation assuaged the fears of whites, but also drew criticism from more militant blacks. His estranged wife, Winnie, accused the ANC of being more interested in appeasing whites than in helping blacks.[239]

More controversially, Mandela oversaw the formation of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate crimes committed under apartheid by both the government and the ANC, appointing Desmond Tutu as its chair. To prevent the creation of martyrs, the Commission granted individual amnesties in exchange for testimony of crimes committed during the apartheid era. Dedicated in February 1996, it held two years of hearings detailing rapes, torture, bombings, and assassinations, before issuing its final report in October 1998. Both de Klerk and Mbeki appealed to have parts of the report suppressed, though only de Klerk's appeal was successful.[240] Mandela praised the Commission's work, stating that it "had helped us move away from the past to concentrate on the present and the future".[241]

Domestic programmes

Mandela's administration inherited a country with a huge disparity in wealth and services between white and black communities. Of a population of 40 million, around 23 million lacked electricity or adequate sanitation, 12 million lacked clean water supplies, with 2 million children not in school and a third of the population illiterate. There was 33% unemployment, and just under half of the population lived below the poverty line.[242] Government financial reserves were nearly depleted, with a fifth of the national budget being spent on debt repayment, meaning that the extent of the promised Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) was scaled back, with none of the proposed nationalisation or job creation.[243] Instead, the government adopted liberal economic policies designed to promote foreign investment, adhering to the "Washington consensus" advocated by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund.[244]

Under Mandela's presidency, welfare spending increased by 13% in 1996/97, 13% in 1997/98, and 7% in 1998/99.[245] The government introduced parity in grants for communities, including disability grants, child maintenance grants, and old-age pensions, which had previously been set at different levels for South Africa's different racial groups.[245] In 1994, free healthcare was introduced for children under six and pregnant women, a provision extended to all those using primary level public sector health care services in 1996.[246] By the 1999 election, the ANC could boast that due to their policies, 3 million people were connected to telephone lines, 1.5 million children were brought into the education system, 500 clinics were upgraded or constructed, 2 million people were connected to the electricity grid, water access was extended to 3 million people, and 750,000 houses were constructed, housing nearly 3 million people.[247]

The Land Restitution Act of 1994 enabled people who had lost their property as a result of the Natives Land Act, 1913 to claim back their land, leading to the settlement of tens of thousands of land claims.[248] The Land Reform Act 3 of 1996 safeguarded the rights of labour tenants who live and grow crops or graze livestock on farms. This legislation ensured that such tenants could not be evicted without a court order or if they were over the age of sixty-five.[249] The Skills Development Act of 1998 provided for the establishment of mechanisms to finance and promote skills development at the workplace.[250] The Labour Relations Act of 1995 promoted workplace democracy, orderly collective bargaining, and the effective resolution of labour disputes.[251] The Basic Conditions of Employment Act of 1997 improved enforcement mechanisms while extending a "floor" of rights to all workers;[251] the Employment Equity Act of 1998 was passed to put an end to unfair discrimination and ensure the implementation of affirmative action in the workplace.[251]

Many domestic problems remained. Critics like Edwin Cameron accused Mandela's government of doing little to stem the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the country; by 1999, 10% of South Africa's population were HIV positive. Mandela later admitted that he had personally neglected the issue, leaving it for Mbeki to deal with.[252] Mandela also received criticism for failing to sufficiently combat crime, South Africa having one of the world's highest crime rates; this was a key reason cited by the 750,000 whites who emigrated in the late 1990s.[253] Mandela's administration was mired in corruption scandals, with Mandela being perceived as "soft" on corruption and greed.[254]

No comments:

Post a Comment